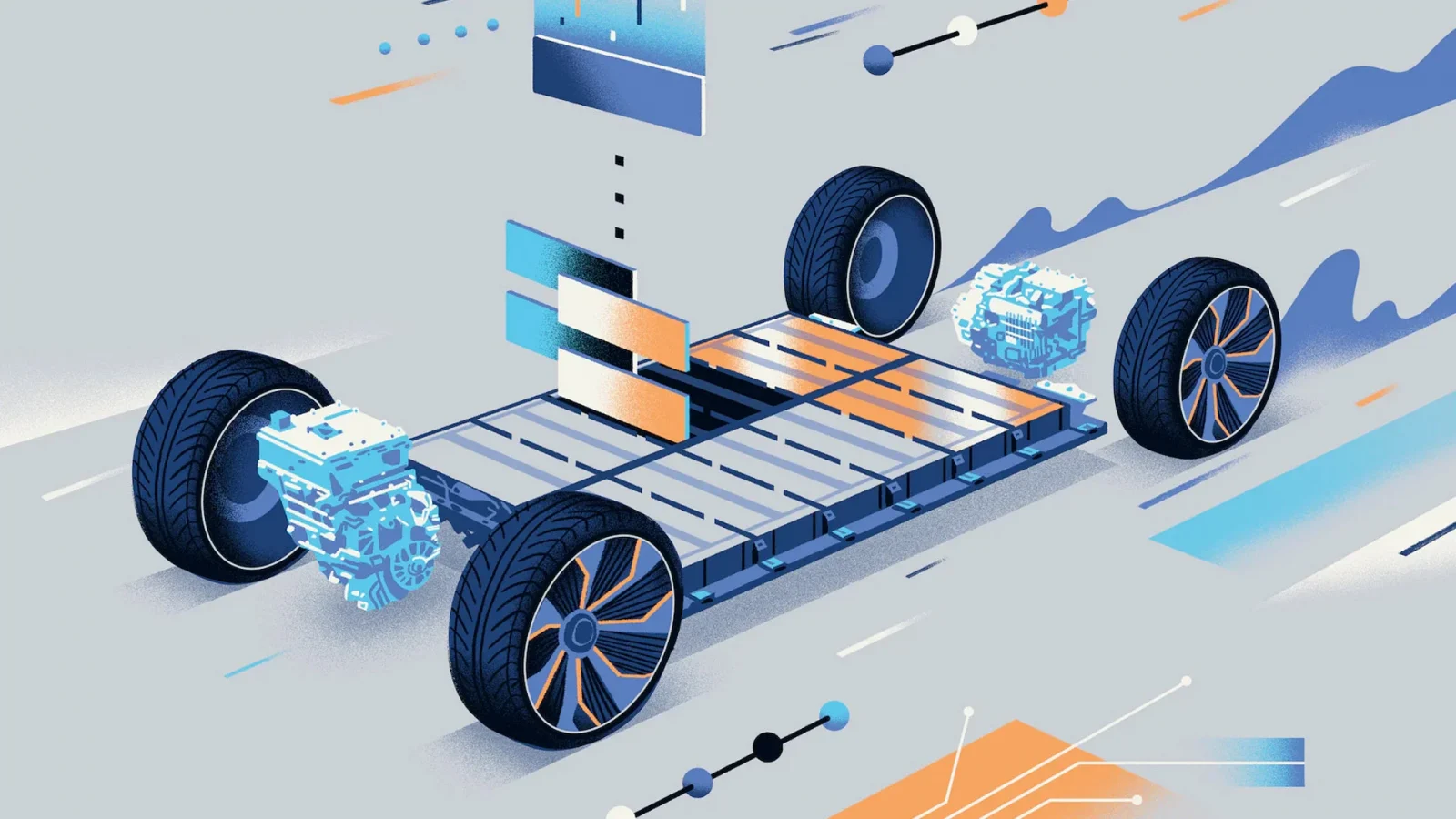

One crucial ingredient for the large-scale switch to electric vehicle usage is unimpeded access to the rare metals that go into EV battery production. News coming out of China suggests that the country is now limiting how much battery metal it exports, casting a cloud over the future of the electric vehicle transition.

It’s difficult to make an EV today without Chinese metal. Now, Beijing is using its mineral advantage to protect itself amid escalating global conflicts. China’s Ministry of Commerce announced last week that it would require foreign companies to apply for permits to receive shipments of raw and synthetic graphite starting December 1, citing national security concerns.

Chinese officials also recently restricted the export of two minerals — gallium and germanium — used for military technologies, virtually cutting off all access. China’s latest announcement might even derail EV manufacturing lines globally — or it could have minimal impact.

China produces about 65% of the world’s mined graphite, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. It also dominates the market for synthetic graphite, made from coal or oil.

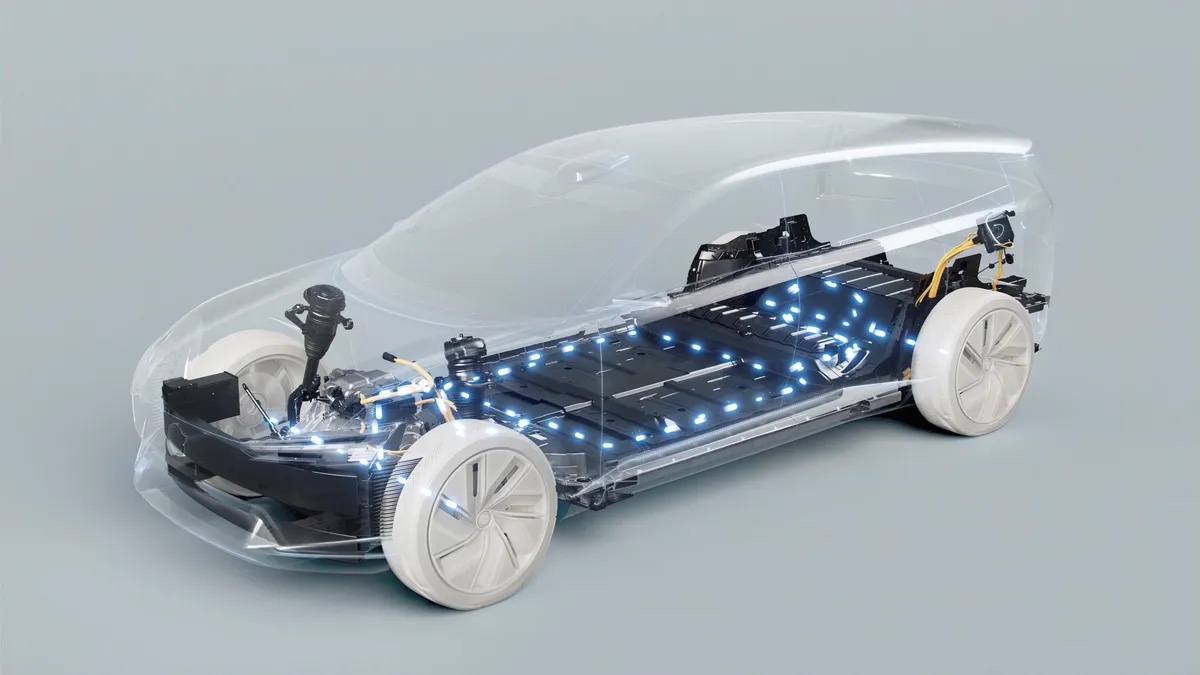

Graphite anodes are used in batteries to enable electric conductivity. To alleviate supply concerns, innovators are trying to replace graphite with silicon and other materials, but that technology is not yet used at a mass commercial scale.

How China’s move affects EV production will depend on what regulators there ask of companies seeking export permits — and how long it takes for those permits to be issued.

“It’s not an outright ban… it’s too early to draw conclusions,” says Caspar Rawles, chief data officer at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. “[But] it could be a significant event if the first permits [are] in 18 months.

“The White House is “assessing the measure and its potential effects,” explains National Security Council spokeswoman Adrienne Watson.

Meanwhile, some members of Congress see the restrictions as cause for further U.S. policy actions concerning China. “This announcement reinforces the need to develop, together with our allies and partners, resilience in our critical supply chains to defend ourselves from this type of coercion,” Mike Gallagher, chairman of the House Committee on China, said in a statement.

China’s announcement came after the U.S. blocked Beijing from obtaining computer chips and Europe declared it would examine potential tariffs on Chinese steel and aluminum.

One other thorn in the China-US relationship is that some EVs made with Chinese mineral supplies don’t qualify for a new U.S. consumer tax credit.

In an attempted remedy, the Biden administration has been investing in at least one alternative source of graphite: Mozambique. But that option is risky too: The mine they’ve bet on has grappled with a violent religious insurgency and labor strikes.

OUR THOUGHTS

With the two wars in Europe now and the very real chance of further escalation, plus the strained U.S.-China relations, it seems as though America and several other major car-producing nations in Europe and Asia need to promptly find viable alternatives to sourcing rare Chinese battery metals. One country should not control the market.